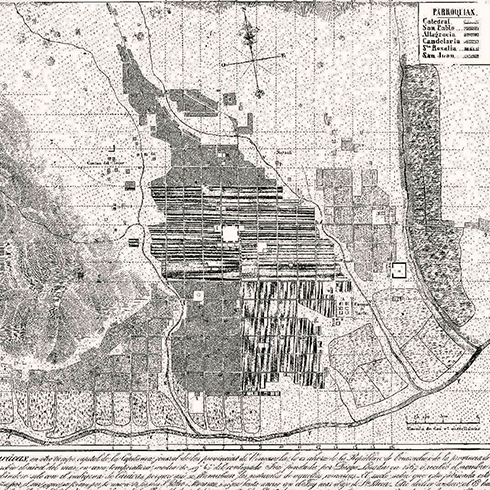

Topographic map of the city of Caracas, 1874.HC-25

Urban Planning takes Power

This plan of 1874 drawn by Estevan Ricard and ordered by Guzmán Blanco is one of those offering more contributions to urban planning, architecture, topography and topology.

Antonio Guzmán Blanco ruled the country from 1870 and his

influence may be stretched as far as 1899. He has been described as an «illustrious despot» and he certainly fits both roles perfectly, as an authoritarian and as a man trying to make his capital city a more civilized and educated place. In his two decades in power one observed one of the periods with greater transformations in Caracas’ history, if we take into account the resources and the population of our city back then. He is perhaps the most accomplished president. If we bear in mind the transformations he introduced and brought forward.

Is evident the amount of importance that Guzmán Blanco places in the city as the result of government work, as an undoubtedly main event resulting from a policy, a strategy that will turn the colonial grid into an urbanism where specially the communications and transportations networks will play a major role.

This plan is titled, as the one before, «Topographical plan of Caracas» with the difference that this time it is actually genuinely topographical. The drawing accurately represents the true measurements of a Square. Caracas is no longer part of that grammar colony of ideal and universal checkerboards,

now the city begins to find its own style, and the first step has been the uplifting of its reality, its specificity. Now the Bolívar Square is the smallest block, as if at the foundation a small town were envisioned but the next block were widened and expanded as to fit a much ambitious city adapting itself to the little streams crossings it and to the hills and slopes in and around it. Caracas is no longer a city whose laws obey a historic edict but rather its own particular geography is finally acknowledged.

Guzmán Blanco takes on from the plan preceding him, but introduces many changes, basically of French Influence. It is not a coincidence that this is the first plan with public buildings drawn: The Legislative Palace, The Masonic Temple, The Venezuelan Museum, and the Central University of Venezuela lay floating on the sheet showing their very new façades.

Architecture’s Independence is achieved and a series of neoclassical proposals are superimposed over the blocks’ perimeters. If formerly the streets were read as a system of continuous walls with doors and windows, now the colonial blocks serve as a support for autonomous façades with new styles. It was an announcement to posterity that as of now, any segment of block or any building could differentiate from each other and become a notorious protagonist in the grid. The church and the corners as a point of reference finally found competition. What was only temporary during the «Investiture of Charles IV» was now permanent.

A notorious case of a building emancipating itself from the original grid would be the Capitol (still a work in progress in the current plan) whose ground floor doesn’t adjust to the edges decreed in the reticule, but consciously generates entrances and exits introducing new possibilities to the street and block.

The Guzmán Blanco Theater (currently Municipal Theater) has not yet been built, yet conditions for its existence are given. The place where the Capitol is being built had been for centuries The Reverend Mothers of the Immaculate Conception Convent; The church of La Trinidad became The Pantheon of Heroes of the Independence, and the Theater’s lot was previously occupied by the temple of Saint Paul, later described as neo classical and built under Corinthian order, which is not strange amongst theaters but in the Caracas of the XIX century it was innovation at its best.

Both the Theater and the Capitol thrive with the ornamental façades and their implantation on the blocks, a new use for the city. The Capitol’s surroundings become boulevards and streets cease to be just utilitarian spaces. By adding trees, statues, fountains and benches they become places of relaxation and commemoration.

The most significant change will take place at the Bolívar Square which will cease being a market and becomes the symbolic epicenter of the Republic, where trees persecuted by Cañas and Merino return once more to the main yard of the city with scenery of the Flag with the equestrian statue of Bolívar at the center.

The celebration of Simón Bolívar’s hundredth birthday will be the perfect event for the city to assume the independence symbols as icons for its public spaces.

We may say that it is the «climatic moment of the grouping, hierarchy, and exhibition of the nation’s memorial in the XIX century» Is the act of putting at the foot of Simón Bolívar’s statue the main republican documents, including decrees, laws, constitutions and the Act of Independence, as the History of Venezuela by Baralt, the Geography by Codazzi, the first census, a copy of each of the Venezuelan newspapers and a topographical plan of Caracas, probably Ricard’s.

We may also see in this plan El Calvario Park, an intervention of great proportions seeking to eliminate the infamous opposition between sacred grid and profane fields, between the city and the countryside. With El Calvario Park a hill pinned to the checkerboard now is part along its domesticated nature of the urban texture.

New Street Composition

In the listing of Public Works made starting from 1870 there is a curious segment: «Street Composition». As part of a «decolonization» of the city’s morphology policy, Guzmán strengthens the tendency to differentiate the buildings that form the block by promoting an edict forcing to paint the façades with oily colors and to substitute eaves by cornices. These varieties of colors and cornices allow us to easily read the limits of each lot. At the same time a cadaster is made expressed in the plan of 1874 drawing a kind of backstitch in the edge of the blocks, a kind of irregular brocade of little rectangles that define the edges of each property.

Till then all the plans of Caracas had represented the block as a robust entity expressed in a single color and with a single texture. But now it is evident a lot composition and a succession of distinct activities.

The city is taking notice of its mobility. Aristides Rojas and Cesareo Suarez propose a Cartesian system whose origin lies on the recently baptized Plaza Bolívar and form the north, south, east and west avenues. It tries not completely successfully to leave behind the names of about 264 corners.

A hygienic campaign starts, to which belongs a 46km aqueduct that comes from the Macarao River, with the elimination of the small cemeteries in Caracas in order to join them to the General Cemetery of the South, inaugurated in 1876.

In that of 1875 there is a list of 14 bridges, all within the city, besides the aqueduct. The plans exclusively dedicated to networks have begun. In 1883 we find the railroad plan from La Guaira to Caracas and the railroad from Caracas to El Valle; in 1884 there is the plan of the Caracas Gas company, in 1885 the General Plan of Caracas Waters; in 1902 a plan titled The Venezuelan telephone and electrical appliances by Ricardo Razetti for the company that had installed the first phones in Caracas.

FFU

HC-30

HC-29

HC-28

HC-27

HC-27

HC-27

HC-26