Zone 1 The founding grid

«The plan of 1578 shows an idealized city and foreshadowed a checkerdboard of 25 blocks, an arranged and uniform grid, church, town hall, plaza, houses and streets. The city started with an order and a plan ».

Federico Vegas

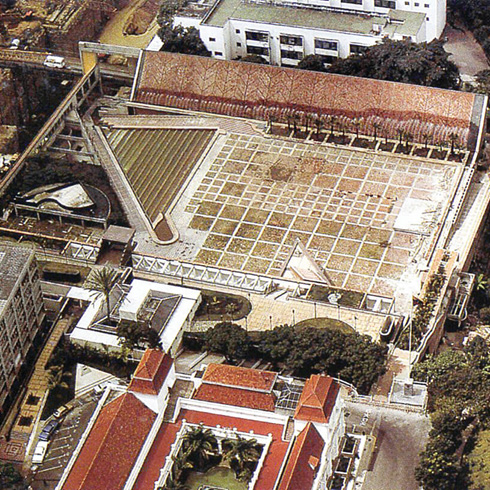

Caracas was one over two thousand cities founded in Latin America in accordance with the «Indies grid» canon. The original grid is a layout of twenty-five blocks of one hundred by one hundred meters, ideally oriented towards the wind and the sunlight, in the San Francisco valley, between the north-to-south Anauco and Caroata streams, with the Guaire River to the south and the Ávila to the north. The Plaza Mayor —now Plaza Bolívar—, began as a marketplace, surrounded by the cathedral and government building in adjacent lots.

Until the late nineteenth century, the city preserved its colonial look. Its modest urban profile, with red clay roofs, was barely touched by Guzmán Blanco’s constructions.

Following the colonial grid tradition, the city was built with continuous borders that led to mixed-use public spaces: the present day Plaza Bolívar, Plaza San Jacinto and Plaza Miranda are examples. The distinguishing feature of the city center is its toponymy: every corner has a name referring to Catholic saints, to persons that lived there or to events that took place there —a unique nomenclature in the Spanish-speaking world, which reaffirms the founding grid in linguistic terms— and forms a collection of anecdotes reminiscent of that small Caracas, of relatively stable population, that saw the birth of a host of personages of paramount importance for all areas of Hispanic American history.

The grid spread out in every direction for decades, until its growth to the west was stopped by a geographical feature, El Calvario hill,—now El Calvario Park— emerged, multileveled, in the best French style3, which determined a fork in the roadway to the city’s exit toward the west and Catia. Caracas was mobilized by streetcars at that time, and enjoyed an average temperature of 21 degrees Celsius.

The urban renewal of El Silencio, adjacent to the park, took place from 1942 to 1945, with low-rise continuous façade buildings with business corridors on the ground floor, supported by belly columns and portals that tried to approach the colonial tradition, as well as common courtyards and gardens for the residents. This intervention eliminated implanted a new standard for public housing, with a great sense of the place and generous internal and external areas, all thanks to the vision of architect Carlos Raúl Villanueva and the extraordinary team of professionals that accompanied him, in his architectural and urban search for the vernacular, from the Banco Obrero4 offices.

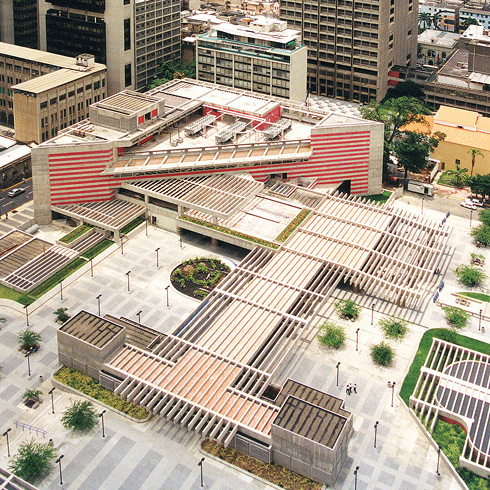

Perpendicular to Bloque 1 of El Silencio, a whole axis of interesting contiguous public spaces spreads out: Plaza O’Leary, across the full width of Bloque 1; a segment of Avenida Bolívar flanked by Bloques 2 and 3 of the complex; Plaza Caracas, longitudinally, between the low buildings (north and south) of the Simón Bolívar Center, which give it a border of yellow marble cylindrical colonnades, until the view is cut off by a low body upon which the twin towers of Centro Simón Bolívar rest.

Form may years the Centro Simón Bolívar towers (1952) became the symbol of the city and defined the modern eastward expansion, through Parque Los Caobos, which scenically continued the axis until Plaza Venezuela. These are segments of the city bearing signs of a grand plan, -the Rotival Plan- designed to control the densification and growth to the east of the city.

The experience of going along the Avenida Bolívar from east to west, plunging into the splendid basements of the Centro Simón Bolívar, strewn with mushroom-shaped columns, and later coming up to the surface and seeing «The Porpoises» 6 posing on the Plaza O’Leary fountains, is one of the great spatial experiences of the city, summing up, somehow, the urban transformation of Caracas and the celebration of its modernity.

Other historical layers are superimposed on the initial grid, with density and zoning that have resulted in punctual buildings amid square blocks, with heights and shapes that break with the colonial profile and the continuous border of the traditional streets. Large scale interventions, like the National Library, are juxtaposed to the traditional small scale city center, and hinder the perception of the charming colonial context. There are also distinguished modern interventions that enhance their surroundings, like the Banco Central de Venezuela, with extraordinary architectural quality, or the Banco Metropolitano headquarters, of elegant design and perfect correspondence with the context; or the Zingg building, with its shopping passage. Toward the south limit of the grid, a large number of houses between party walls and with courtyards survive deterioration without much success, coexisting with nondescript condominium buildings, built after the seventies and that break the parameters of the founding city blocks, of continuous borders and low height.

The flavor of the traditional city, with its founding grid, is captured in the street layout, which remains untouched, despite the different formats of architecture and urbanism that were superimposed on it, attempting to destroy an original memory. By retaining the names of each one of its corners, it fought a false idea of progress and modernity that tried unsuccessfully to erase it from the map.

Avenida Bolívar en 1953. FFU

Avenida Bolívar en la actualidad. AMU

Valor Coral El Conde AMU-1

Detalle del Banco Central de Venezuela. A-TS

Valor Coral La Pastora AMU

Vista aérea de La Pastora. RL

Plaza Mayor de Caracas. Detalle la pintura Nuestra Señora de Caracas, Juan Pedro López, 1776. DF-01

Parque El Calvario. DDN

Parque Los Caobos. YPM

Conjunto El Silencio. DF-02

Bancaribe A-IU

Diosa de la ciudad JAC

Toponimia del damero DF-03

Valor coral en fachadas de El Centro YDB

Vista aérea de La Pastora. RL