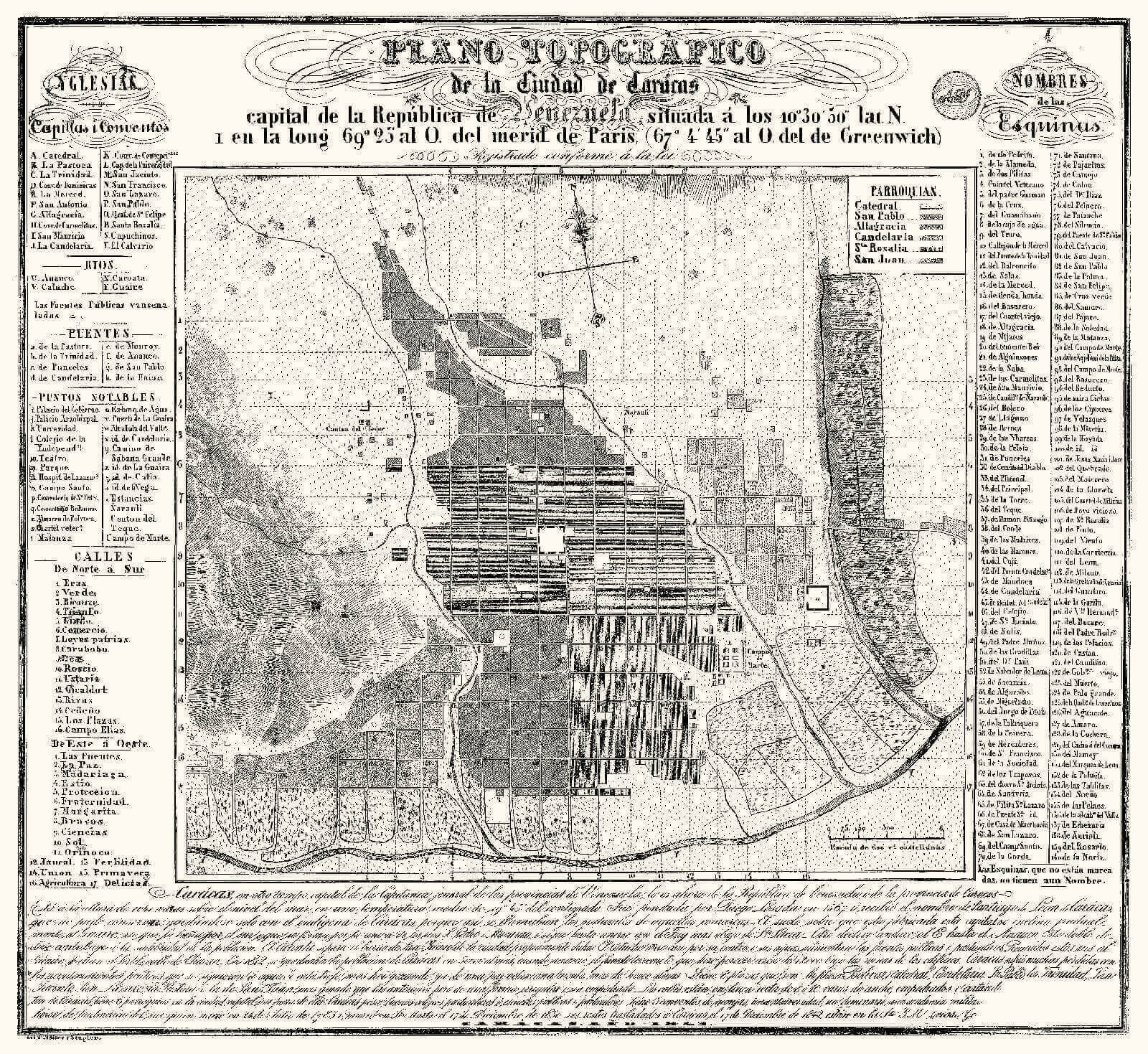

Topographic map of the city of Caracas, 1843. Litograph by Müller & Stupler.HC-18

A small greatness

How to explain that in one of the most modest cities in Spanish America sprung the seeds of an independence movement capable of subduing colonial power in the heart of 2 out of 4 viceroyships?

Maybe the Captaincy General of Venezuela had become unexpectedly rich, once cacao and coffee trade grew in contrast with mining economies that were exhausting themselves elsewhere, and this growing prosperity had no time to transform itself into urban expansion and architectural grandeur, but rather into new ideas professing another sort of expansion. Projects so spiritually ambitious sprung forth that could not be contained in such a small-scale city, and would end sacrificing its expansion and development.

One vision of the latent tension that hung in the air may be found in the writings of Humboldt, who visited Caracas in 1800:

The valley’s scarce extension and the proximity of tall mountains like Ávila and La Silla gives the location of Caracas a gloomy and severe scenery, especially at this time of year when the coolest temperature reigns, during the months of November and December. The mornings are then of great beauty; with a clear and serene sky the two domes or pyramids surrounding La Silla may be seen as also the jagged crest of Mount Ávila, later in the afternoon the atmosphere charge, mountains are filled with mist, streams of vapors are seen hanging above the always green hills, dividing them into superimposed zones. Little and little these zones seem to merge and the cold air that descends from La Silla dissipates in the valley and condenses the light fogs and makes them thick clouds.

Nearly a century separates the plan of 1775 and that of 1843 we are about to review; however it hardly looks as if the city has been developed, in fact it seems to have been reduced. This dramatic and paralyzing reduction was inevitable due to the intense earthquake in 1812 and the long, hard and exhausting wars culminating with the independence of 5 nations. Out of 50,000 inhabitants in 1812 we were down to 40,000. Caracas gave its best men and resources to the cause and it would be long until it could seize its new destiny, emancipation. One would have to wait until 1870 for the city to have at least the same population as before independence and to rebuild the monuments and buildings that the earthquake tore down.

A Formal Independence

At the northern angle of the sheet there is a seal with the initials of Angel Jacob de Moises Jesurún (1824-1893). It is the first time that a plan of the city is printed by one of its own inhabitants.

This 1843 plan was printed in the lithography of Johann Heinrich Müller and Guillermo Stapler. The story of these German technicians that together with Georg Lauer and Federico Lessmann brought new techniques and equipment to the country is intimately connected to the shaping of the Venezuelan printers, draftmen and photographers that would take on the task of representing the city from the later parts of the XIX century to early XX.

In 1843 the presidency of José Antonio Páez ends, followed by Carlos Soublette’s. The presence of two Independence heroes ruling the country makes us think that the city would change radically but in Jesurún’s Plan the republican spirit in Caracas may only be seen in the new street names.

One may also find, perhaps for the first time, a list of all the corners in Caracas, a curious and absurd two-century old tradition of giving city’s addresses. For this strange and village-minded way of giving addresses, the corners took their names from buildings or historical facts, making the list look like a book of stories and secrets: «Tío Pedrito» [Uncle Pete], «Dos Pilitas» [Two water boxes], «Water Box», »Truco» [Trick], «Viento» [Wind]. On an urban landscape of 25 Blocks 36 corners would have to be named instead of just naming 12 streets. Jesurún’s plan tried to put an end to this use by giving streets names that would thrive under the spell of the patriotic environment, such as «Ricaurte», «Triumph», «Patriotic Laws» were given, a nomenclature that would soon be forgotten.

It is evident that City Planning is still the same as in the colonial period, in fact it is accentuated. Jesurún draws an abstract, perfect city, with identical blocks. The axis on the streets look like a meridians and parallels system extending the surrounding nature, including in the checkerboard the vacant lots, fields and dumps as if warning that their inevitable fate is the checkerboard.

There is a similar phrase regarding the foundational one from Pimentel («Out of this the whole town is filled»):«The unmarked corners are only so because they still lack names». We are looking at an exaltation of the grid that reaches a graphical climax. The topography laid subdued by a rigorous urban scheme suspiciously decided.

The absolute idealization of the old colonial scheme prevails in the plan as if it had been martially conquered. There is an example in the Plaza Mayor or Main Square sublimating governor Ricardos’s work by drawing arcades in all 4 sides of the square, when one only saw them at the northern and southern faces.

A new question arises: What sort of continuity did the young republic give to the urbanizing enterprise that Spain decided for America? The answer is «not much». The country was exhausted and had no energy or resources to transform its cities or fields.

Jesurún’s plan reveals the urban remains of this terrible conflict, a city exhausted and crushed represented as a republican abstraction of a colonial grid. Soon the first attempts would be made to change this paralyzed face of the city.

HC-19

HC-20

HC-21

HC-22

HC-23