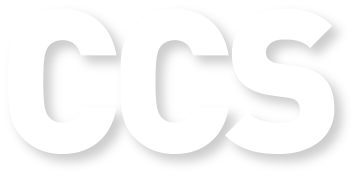

Caracas Plan, 1929. Ricardo Razetti engineer. Comercio, Lithography and typography.FFU

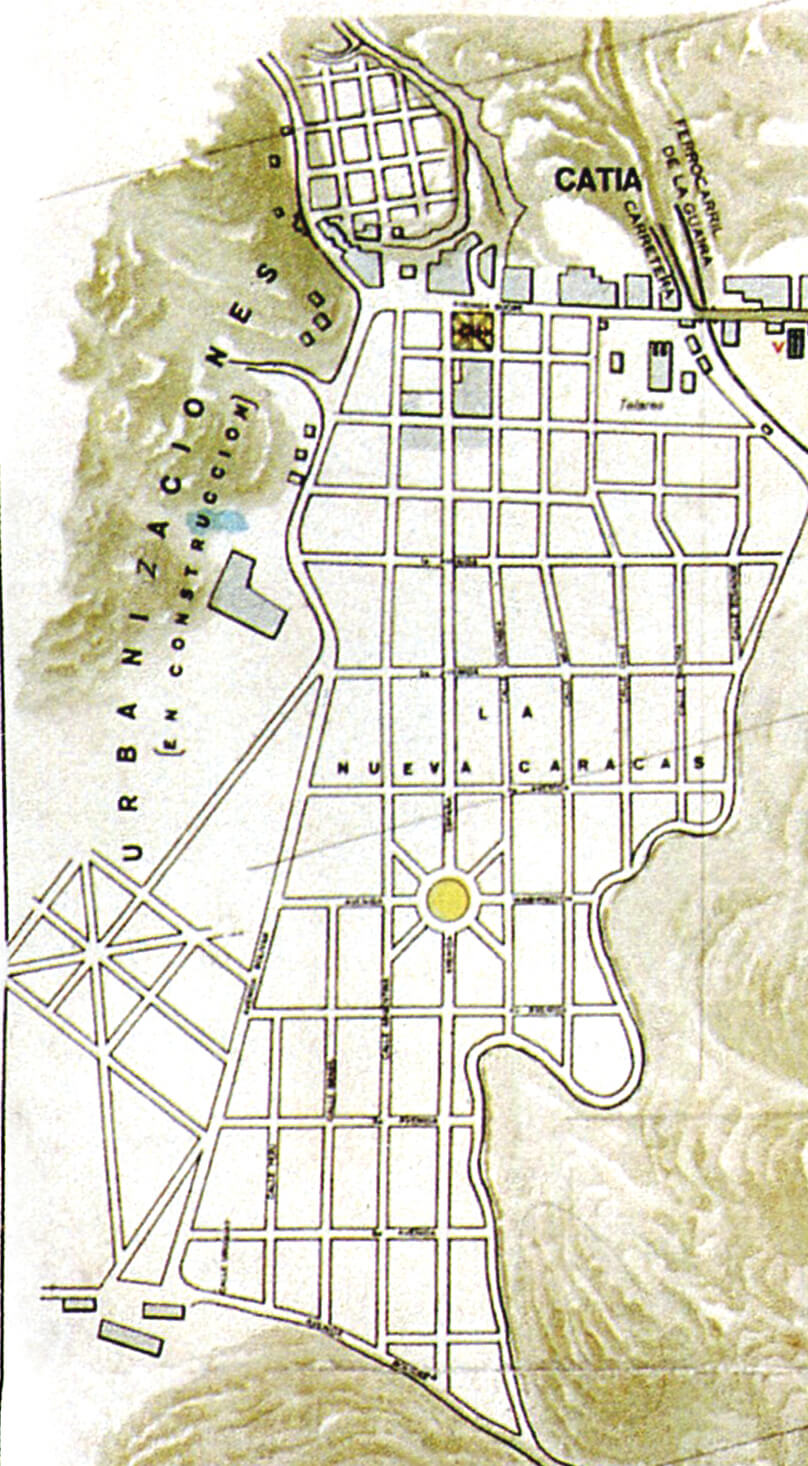

Ricardo Razetti offers his last representation of the city. The neighborhood of «Nueva Caracas» (New Caracas) appears with a subtitle that is a bit unusual to find in these plans («under construction»). Its extension is equivalent to 80 of the traditional center’s blocks. Given its scale and novelty it is, proportionally, Caracas’s most important intervention. Meant as a satellite city, separated form Caracas’s core by the long arm that stretched into La Guaira, it was built for the working class: a specificity that differs from the multifunctionality set by the colonial grid. Disintegration and zoning criteria were beginning to manifest. Nueva Caracas will be the great valley’s entrance from the sea, having the multiplicity and vitality of a port docked in the mountain. It was there, that immigrants, pre and post war, found a new home.

The plan shows Los Caobos Park, El Calvario’s successor. Caracas’s grid dares to go further from one of its historical limits, the East, vehemently marked by the Anauco brook. This park will favor a new recipe for urban development: Now, growth won’t take place by blocks blooming among Plazas, but instead, by neighborhoods blooming among Parks.

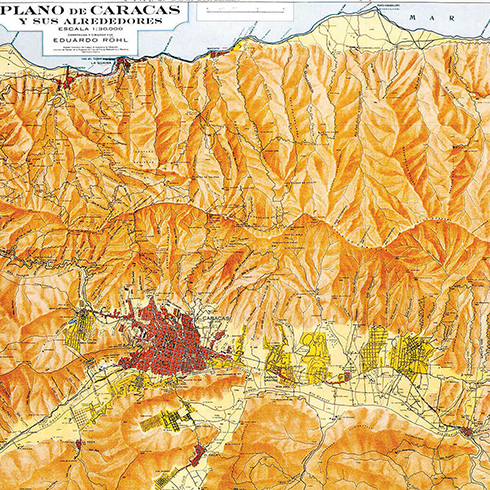

San Agustín del Norte appears as an interesting modification of the original reticule’s expansion, when proposing to divide the traditional block into four smaller ones. This proposal gives continuity to the existing streets and does not interrupt the tissue’s uniformity. Some important changes, however, were raised, since there will be an emphasis on the use of housing and the automobile. Note the photograph illustrating the fact that there is room, in the new street, for up to five cars. It is the prologue of an urban growth that will be dominated by the residences known as «quintas» and automobiles (two 1930 plans are dedicated exclusively to showing the address towards which the streets lead, and the street corners’ names, as witness of a city dominated by the «automobile lifestyle»).

Razetti’s plans, as Padrón says in the quoted essay, prefigure the city’s growth by drawing the tracing of the easternmost neighborhoods, before they were rebuilt. Razetti intervenes in the Saint Augustine project, built by Luis Roche and Juan Bernardo Arismendi, and includes it in a 1911 plan, when it was actually built ten years later.

In an advertising filled plan from 1928, San Agustín del Norte is promoted for its centrality; showing us that being near Plaza Bolívar was still considered as an important asset. The

modernity of these houses is also praised, with an appearance celebrating an eclecticism that goes from a Moorish style to Art Nouveau, and avoids continuity in the façades; appealing to a subtle desire to live in quintas such as those of El Paraíso .

The success of private promoters led the Workers Bank (Banco Obrero) to build a second, more modest version, south of the Guaire: San Agustín del Sur. Once again we have a grid, but this time, one that’s more adapted to the geography, with a form and orientation of its own, autonomous and morphologically detached from the rest of the city.

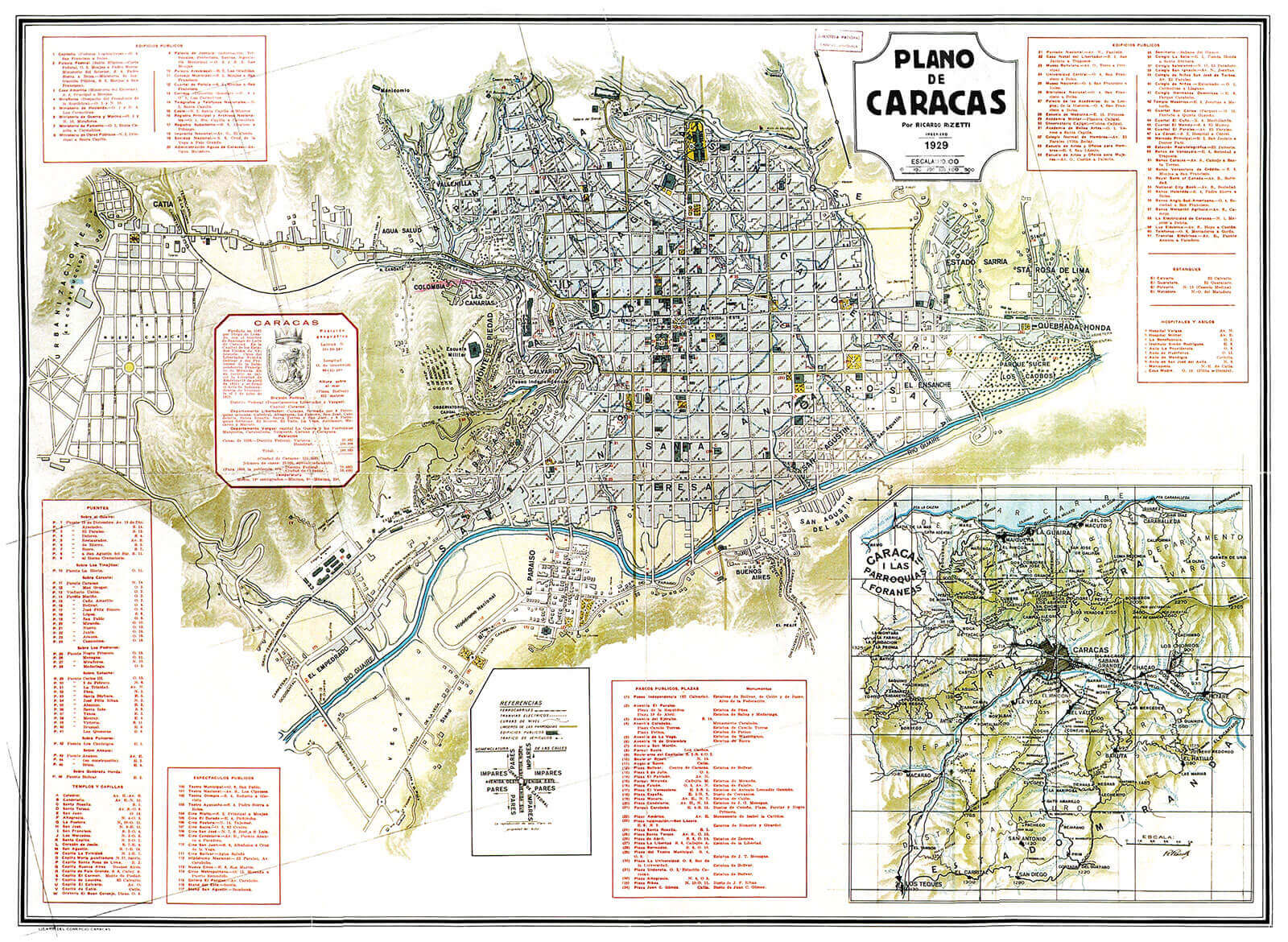

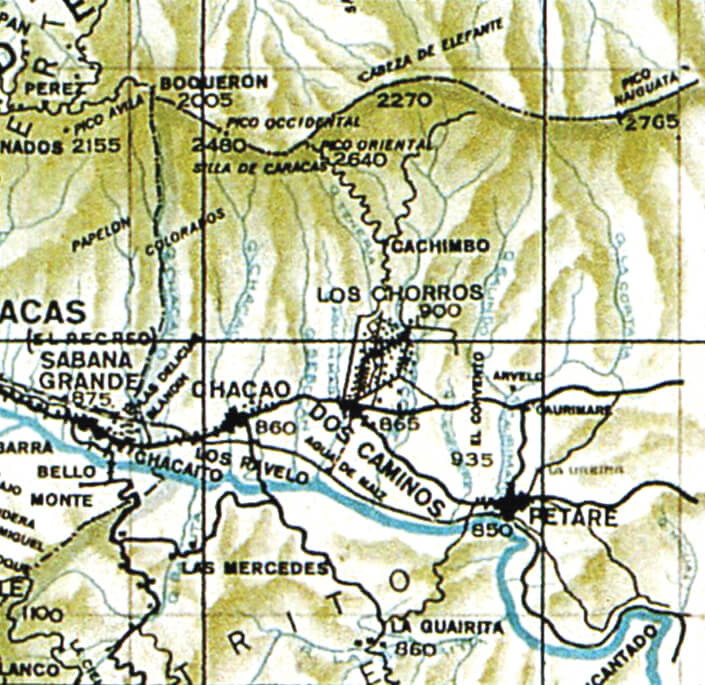

In a border of 1929’s plant we see a small map titled: «Caracas, las parroquias foráneas» (Caracas, the foreign parishes). That reminds us of 1578’s plan with its superposition of a city plan over a map of the central region, including the mountains and the coast, and of course, Razetti’s own 1896 plan.

In this new version, Razetti shows us with greater detail, the system of Caracas and its neighboring towns, those that throughout the XX century are going to be engulfed by the metropolis most of them also based on checkerboards: Chacao, Petare, Antímano, El Valle, La Vega, Baruta, El Hatillo and Los Teques, to the South; Maiquetía, La Guaira, Macuto and Caraballeda, to the North and the coast.

A special case is the rural neighborhood of Los Chorros, with a El Paraíso like urbanism, yet in this case conceived, at least initially, as a place for a second house away from the city.

As to nomenclature, in 1911 Razetti had already drawn a plan joined by a 1910 communication to the Municipal Council in which he explained his purpose: «Today’s boundaries are the same as to when the city, low on population, was naturally divided by crossing brooks… Constructions today cover most of these brooks, making these boundaries neither visible nor precise»; therefore making a new «denotation of boundary lines through streets and avenues» absolutely imperative. In spite of his being right, Razetti was right yet, regrettably, he was not evaluating the loss of the natural resources offered by the brooks’ system. This natural network that preceded the city’s foundation and was able to form a system of Parks and identifying the different parishes would begin to be erased definitely. The biggest problem, however, was not the lack of legible and functional limits between the parishes, but the fact that these would no longer be the dividing or defining structures of the city. In this last Razetti plan, drawn in 1929, we may see eight parishes pointed out, but there were developments that neither belonged nor gave continuity to this tradition, such as El Paraíso, the so called «State» of Sarría, the quoted (still under development) Nueva Caracas, or more informal settlements like El Guarataro. The city will face an expansion period without a system of spatial organization or the criteria to determine its parts, and since then, will lack a common nomenclature to give cohesion, coherence and organization.

FFU

HC-40

FFU

FFU

FFU