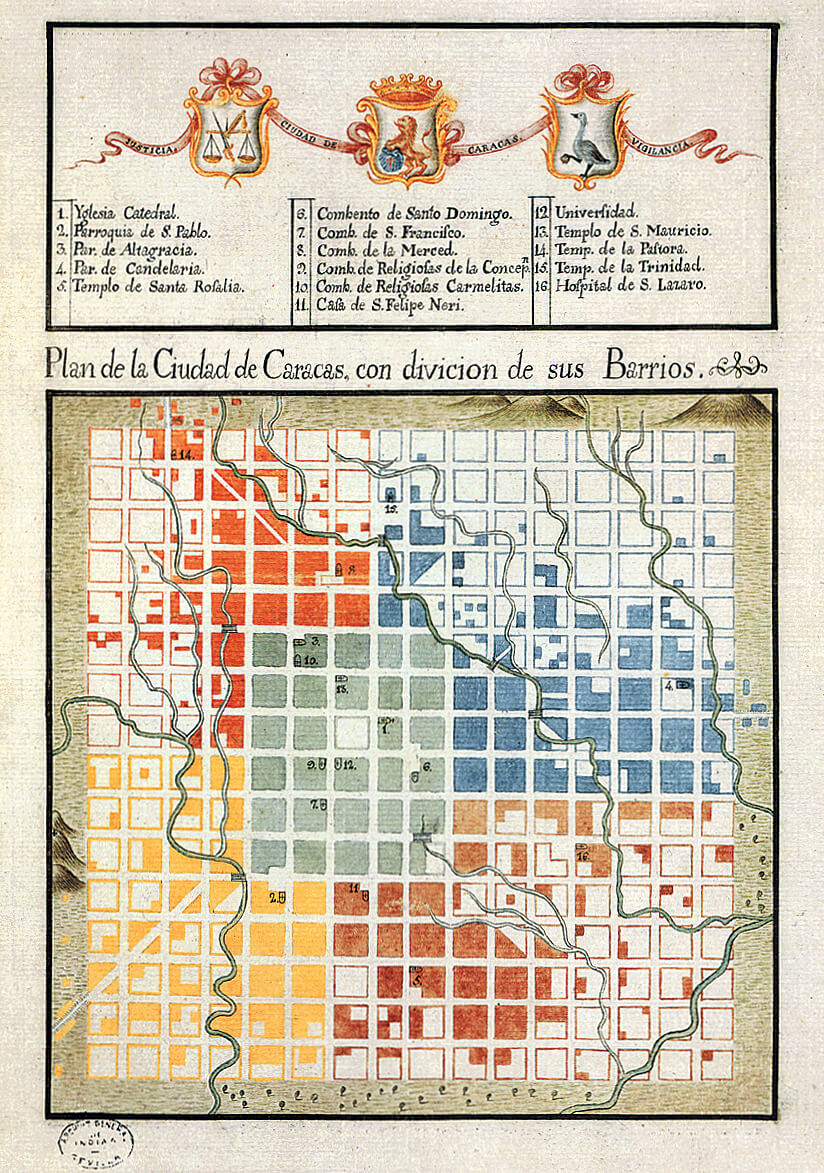

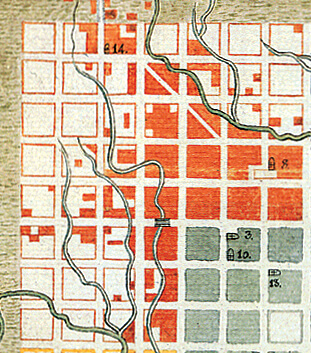

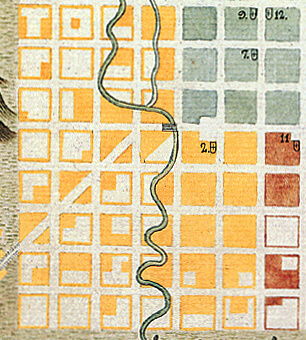

Caracas City Plan, with neighborhoods divisions, Joseph Carlos de Agüero, 1775. Archivo General de Indias.HC-14

The perfect checkerboard and the profane nature.

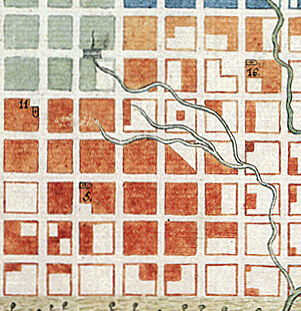

Half a century later a plan called «Plan for the City of Caracas, with a division of its quarters» was drawn. In it we may observe a city shown on a perfect square of 16×16 blocks. These 256 squares had grown as established in the quoted phrase of the first plan: Thus is whole town is filled.

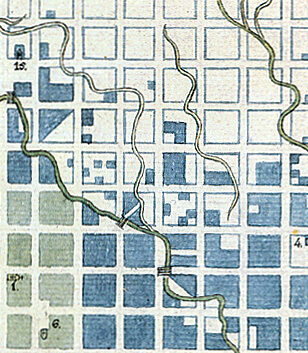

The Grid keeps being omnipotent and equally idealized. All the blocks in this plan have the same length and shape, when in reality they would necessarily show variations. Nature has no longer any presence, we barely see streams seeming to cross the checkerboard without affecting it, as if they didn’t occupy the same space, and some timid symbols of mountains to the North and West.

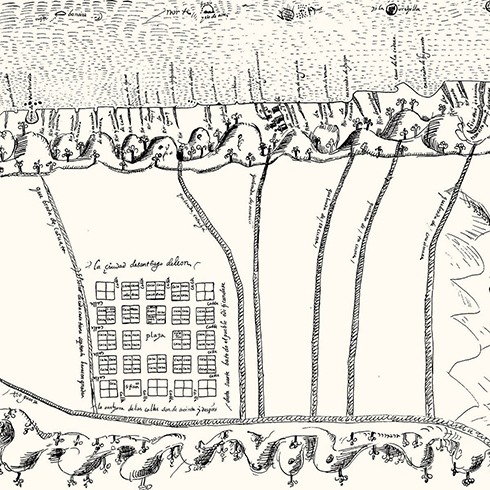

The ceremony of the founding of Caracas and any other Spanish-American cities included the rite of cutting a bush with a Sword. That incipient and minimal urban block, surrounded by an infinite landscape, was then attacked. Any misstep. and branches would climb through windows, settle above rooftops or hide

entire walls. The first skirmish was against the cují (Prosopis juliflora) abundant near the slopes to the east and south of the primitive city; enough to be considered the cause of some epidemic so it was decreed a public enemy and was persecuted for many centuries.

In the colonial history of skirmishes between city and nature no one surpasses Governor Francisco Cañas y Merino who ordered that all trees in Caracas were cut down. His sanitary campaign was ruthless against the cují but avocado, plantain and orange trees were cut down as well. A small army would go to the backyards or front yards of houses and would leave them so barren that only the sun had a place thereafter.

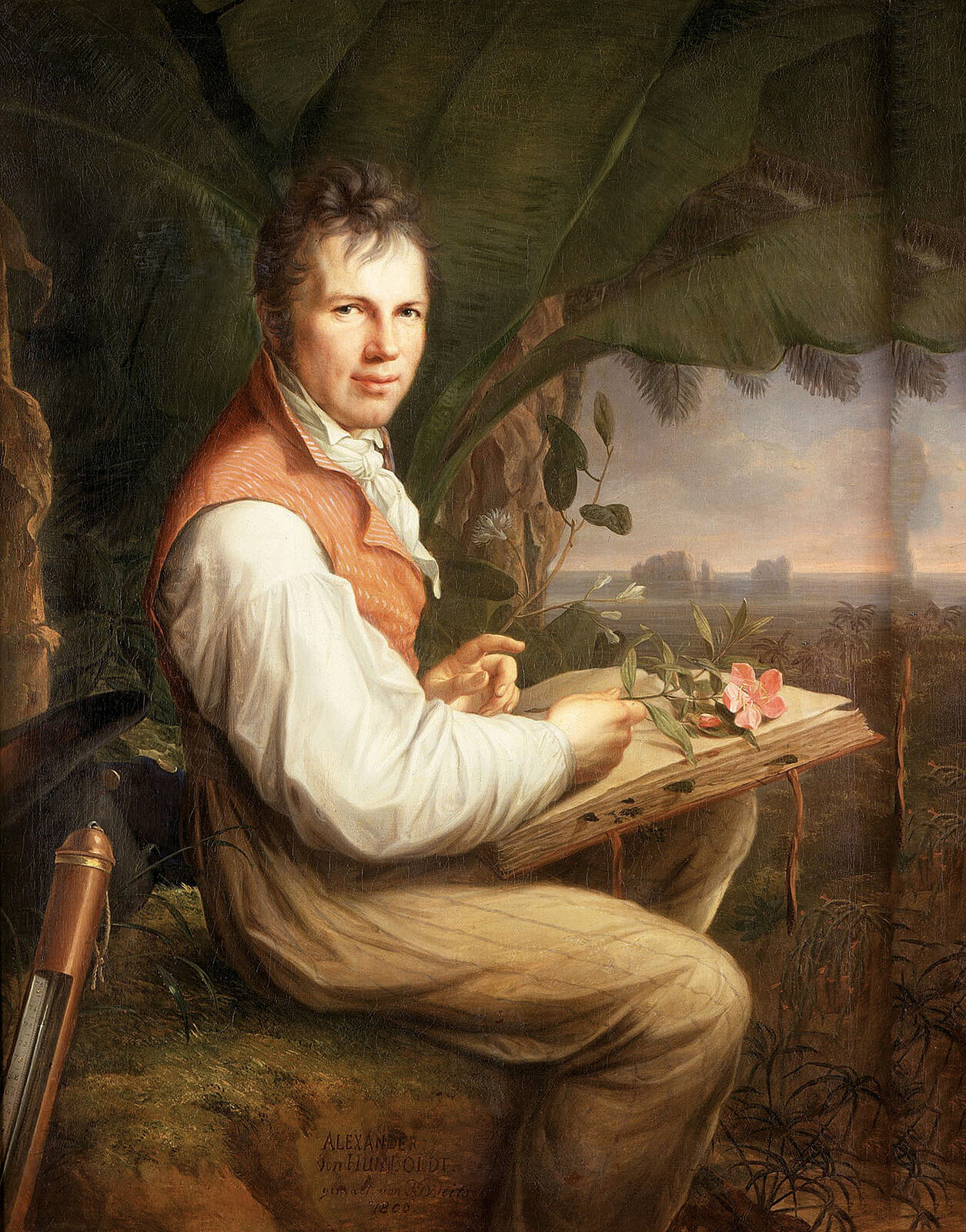

The Attorney General, Don José de la Plaza was incarcerated for having a frangipane tree in his backyard. This would explain why Humboldt asked himself, a century later, why there were no secular trees in Caracas.

How to divide the city?

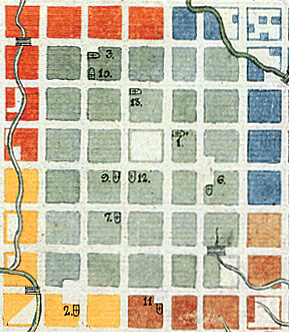

Ignacio Sola Morales explains in one of his essays that topology is the landscape of concepts and topography the description of a specific landscape. Maybe the most topological thing in this plan is found with the use of colors: Green in the center for the parish of Catedral, Orange for the parish of Altagracia, Blue for La Candelaria, Yellow for San Pablo and Sepia for Santa Rosalia. Which concept was he trying to establish? A letter joining the sheet reads:» It is deemed useful, convenient and necessary to create 8 quarters each with its own Mayor so that the city would be divided proportionally into blocks». It is clear that the division in colors is part of an elaborate strategy already announced in an ornamental ribbon on the superior edge with the words «Justice» and «Vigilance»

The structure of the city becomes confusing due to the coexistence of such words as «barrio», «parish», «mayoralty», «council» and «town hall» A confusing juxtaposition that will keep growing until now when the modern terms of municipalities, communities and neighborhoods [called «urbanizaciones»] appear. It is confusing, up to the point that today we still do not have a universal and widely accepted nomenclature for the structure of our city.

Each one of these «quarters» keeps the same proportions, functions and laws of growth as in the rest of the grid, including a square and church in its center. There is some kind of urban criterion of continuity, homogeneity and legibility between the parts and the whole. At the same time, the Caraqueño finds a minimal unit of scale for referring to himself. He is a citizen, also a neighbor and a parish man.

In the index besides there are temples, convents, a university and a hospital. A variety of typologies begin to take shape, but these do not exist as autonomous entities but rather as marked and bounded by the blocks. Especially with the housing, whose shape and functions represent a micro cosmos of the urban, in view of the fact that the relationship between house and yard is akin to that of blocks and squares. As Aristotle claimed: «The state is by nature clearly prior to the family and to the indi-

vidual, since the whole is of necessity prior to the part». Also León Battista Alberti in the XV century: «… as the philosophers maintain, the city is like some large house and the house is in turn like some small city…»

Dream and reality

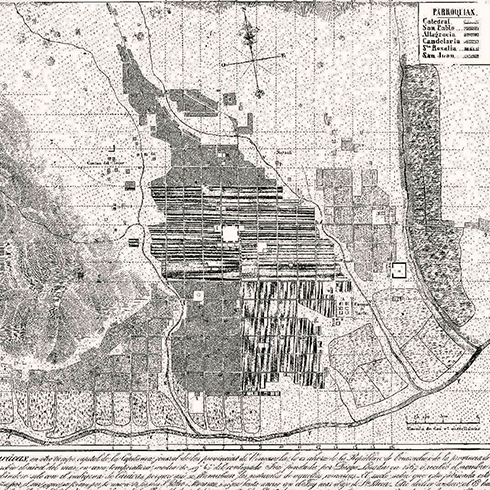

In her essay The Investiture of Carlos IV. Baroque scenery for the XVIII century’s Caracas, Rosario Salazar describes Caracas in 1789. Centered in the remodeling of the Plaza Mayor (Main Square) in 1753 by Governor Felipe Ricardos, who built fountains, staircases, porticos and shop sites on the southern and western façades, according to engineer Juan de Goyangos’s project, maybe the first one to reorganize public space in Caracas.

To all these constructions provisional facilities for the festivities of 1789, would be added, 40 years later, ranging from painting and sculptures to stages, benches and false façades that would give humble Caracas the aspect of a Big City. In contrast with this «prospective or false façade» resources Salazar describes the deplorable state of waste water networks, lighting and above all, the ruinous state of roads in and out of Caracas.

Caracas was debating between what is bucolic, primitive and hazardous. In 1764 José Luis de Cisneros, an agent of the Guipuzcoana Company describes the «Abundant and delicate waters of 4 rivers coming down from the first mountain range and run through most streets and impregnating many gardens». These channels coming from the Catuche River that ran through all blocks north to south were great for harvests, but not for the complex life of a city harassed by constant rain.

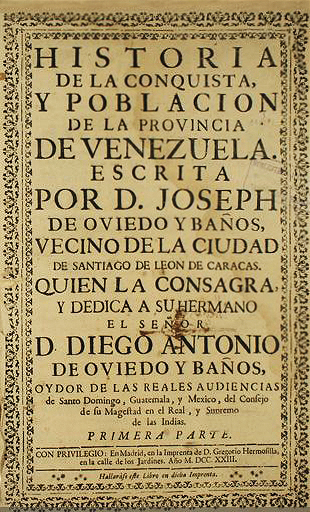

The Caracas represented in this 1775 plan had reached its maximum development as a modest colonial Spanish American city inhabited by an agricultural society who survived pests and the devastation of a major earthquake. It has also the heritage of its own history, creole and epic, narrated by José de Oviedo y Baños, written in 1723: History of the conquest and population of the Venezuelan Province.

Everything is promising. The colonial public powers that were separated and performed at different places before, will slowly drift towards Caracas and coincide in it. In 1776 the Venezuelan Intendancy is created, ruling over administrative and fiscal matters. In 1777, these were The Captaincy General of Venezuela and in 1786 the Royal Audience of Caracas. Our city would no longer depend on Santo Domingo or Bogotá for administrative matters.

This centralization of executive, military, judicial and administrative power will coincide with the boom of cacao and coffee trade. The scene is ready to set on a type of growth that would allow Caracas to dream with the scenarios and prospective seen in the false pretentions of the Investiture festivities, pretending to be a city it never was. Some streets are widened and in some cases nature is a welcomed guest, seeing as how houses once again have vegetation in their yards, there is even one avenue with double rows of trees.

The Caraqueños could not imagine the glorious and bloody future awaiting them.

La-Pastora

Parroquia-de-Catedral

Parroquia-de-Candelaria

Parroquia-de-Santa-Rosalía

Parroquia-de-San-Pablo

HC-15

HC-16

HC-17