Zone 4 La Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas

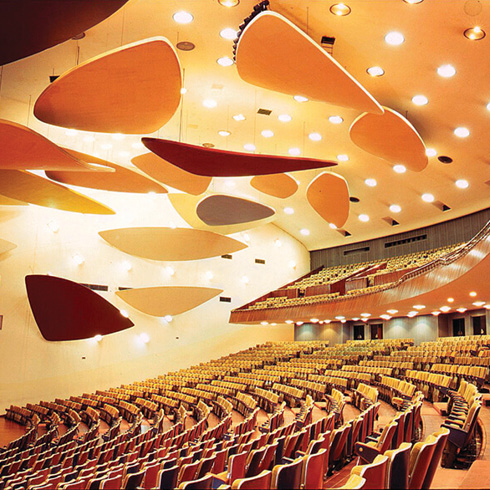

In 1942, President Isaías Medina Angarita created the Autonomous Institute of the University City of Caracas (UCC), in view of the fact the Vargas Hospital could not cope with the city’s demand. Carlos Raúl Villanueva —a Venezuelan born in London and educated in the Ecole de Beaux Arts of Paris— began working from his office at the Ministry of Public Works with the first drafts of the University’s blueprint, beginning with the planning of the University Hospital. The UCC would quickly turn into a personal laboratory of sensory experiences within the idea of a garden city, which varied from a classical layout in its first stage, to the principles of modernism in its second stage. The segregation of uses, the independence between sidewalks and roadways, the continuous green as the visual extension of the landscape; the fifth façade or the use of the rooftops, the personal innovation of including art to the architecture, and the exploration of public space by covering the open spaces, even with vegetation in some cases (palmetum); or the sidewalks, which are covered by audacious structures that can be seen in folded, curved and even flat shapes; these are some of the most notorious personal achievements. It was granted a World Heritage status by UNESCO in 2002 because of its important contributions to architecture, urbanism and to the synthesis of the arts «…the creation of a new architectural-pictorial-sculptural body with no evident fissure between its different expressions», thus accomplishing a truly overwhelming spatial and aesthetic experience. UNESCO’s declaration includes 87 buildings of different schools and 87 works of art. The Botanical Garden, rescued as a component of the World Heritage since 1999, treasures the grandest palm collection of Latin America, having also a beautiful building for the herbarium, and an auditorium with two allusive murals by Lam and Narváez. From an urbanism perspective, two different plots can be seen: one with a symmetric order that goes from the Clinical Hospital to the rectilinear hallway with flat roofing (across from the Central Premises), showing figurative art applied to the school of medicine’s buildings; the other, with a modern order disposition, in which orthogonal buildings —meant to house classrooms— are randomly combined with other unique buildings —given the shapes and ceilings— meant to be used as amphitheaters, workshops, libraries, and/or sports stadiums. A laboratory of reinforced concrete shapes with mosaic details from Bizaza (Italy), with great walls of solid colors or murals, which are combined with innovations that encompass covered plazas and sidewalks, interior gardens, intermediate spaces of transition between the exterior and the interior, as well as enclosures as light as lace –concrete lattice– that allow the green to flow in a continuous manner; the integration of light and vegetation. The Central Premises, which are the heart of the University City, are placed in a north to south direction perpendicularly to the axis of the hospital, thus breaking all previous symmetries. These are comprised of the Rector’s Office and its square, the Covered Square, the Paranymph, the Concert Hall, the Library, and the Aula Magna, which treasures Calder’s clouds decorating the hall’s ceiling with gigantic colored scales that serve as acoustic panels. This «heart» functions as a unitary whole because of its singular use of roofed public space as a link between the elements, which are placed randomly following their own structural systems, turning the covered plaza experience into something unprecedented. In the artists hall, where sculptures (by Laurens, Arp) and a series of murals showing large scale mosaics can be found (by Léger, Vasarely, Navarro, Manaure, among others), the elements alternate and incite movement between them along the shafts of light that hold an exuberant vegetation. In the lobby across from the Concert Hall, the architect opens a hexagonal zenithal orifice that complements the Positive-Negative sculpture (by Vasarely) and a two-tone ceramic flooring showing the same figure. Once a year, the light is cast in a way that causes the prints in the roof and in the flooring to match. From there, one may see both the stars and the Central Library building (red and black), this being the best example of the synthesis, according to experts. This design vocation develops in the following buildings. The classrooms give the occasion of unfolding the light protecting parasols in the high façades (Architecture, Odontology) and, conceptually, the more modern classrooms are openly linked to the exterior with gardens and inner patios that go from wall to wall and from roof to ceiling. The auditoriums, libraries, workshops and exhibition areas are a motive to the plastic search of new shapes with the material of the time: concrete. The combination of elements of mobility (ramps), roofing, and art (murals) blurs the limits between the architecture and the plastic experience (Faculty of Humanities), which repeats itself all over the campus. The spaces and transition elements, between the interior and the exterior, reach unique interpretations that materialize themselves in spaces with pergolas (Odontology), or in autonomous marquees that are overlapped by other buildings (Rector’s Office, Museum). Villanueva experiments with light as a construction element, with which he horizontally draws separations between roofs of different heights, diagonally cuts through pergolas, takes advantage of the verticality of its fall through light shafts for the inner gardens, and cuts it in different shapes with concrete lattice walls. The Faculty of Architecture, one of the last buildings designed, gathers the best experiences. A horizontal opening that allows the Ávila to be seen from the entrance; the beautiful double curvature roofs in the plastic workshops (Taller Galia); the amphitheater classroom with folded shape ceilings and the façade with the abstract murals in tones of blue by Alejandro Otero. The ground floor groups all the concepts of modern space and highlights important works of art of a minor scale from artists such as Alexander Calder, Gego, Soto, Narváez, and murals of priceless beauty from Valera and Manaure. To the westernmost part of campus, the sporting facilities —football, baseball, basketball, and swimming pools— contrast with shapes of shells that stand out in the urban horizon, rising from the city with their exterior edges that announce the existence of an architectural laboratory of spatial experiences that, without a doubt, reaches «sublimity». UCV’s rental áreas at Plaza Venezuela, develop the only great urban Project of the city; as well as southern rental áreas in front of Las Tres Gracias square. Both generate incomes dedicated to fund academic research, as Simón Bolívar anticípate with his legacy.

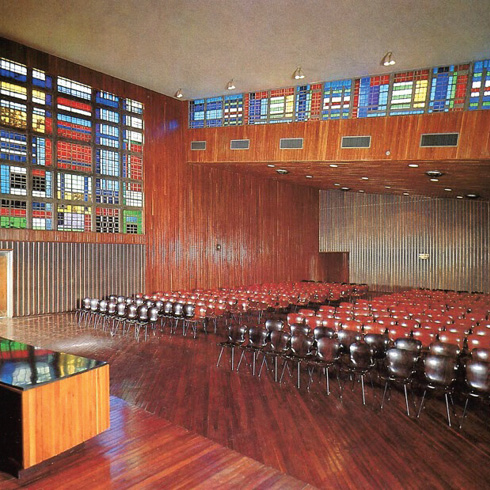

Aulas anfiteátricas, Facultad de Arquitectura y Urbanismo. YDB

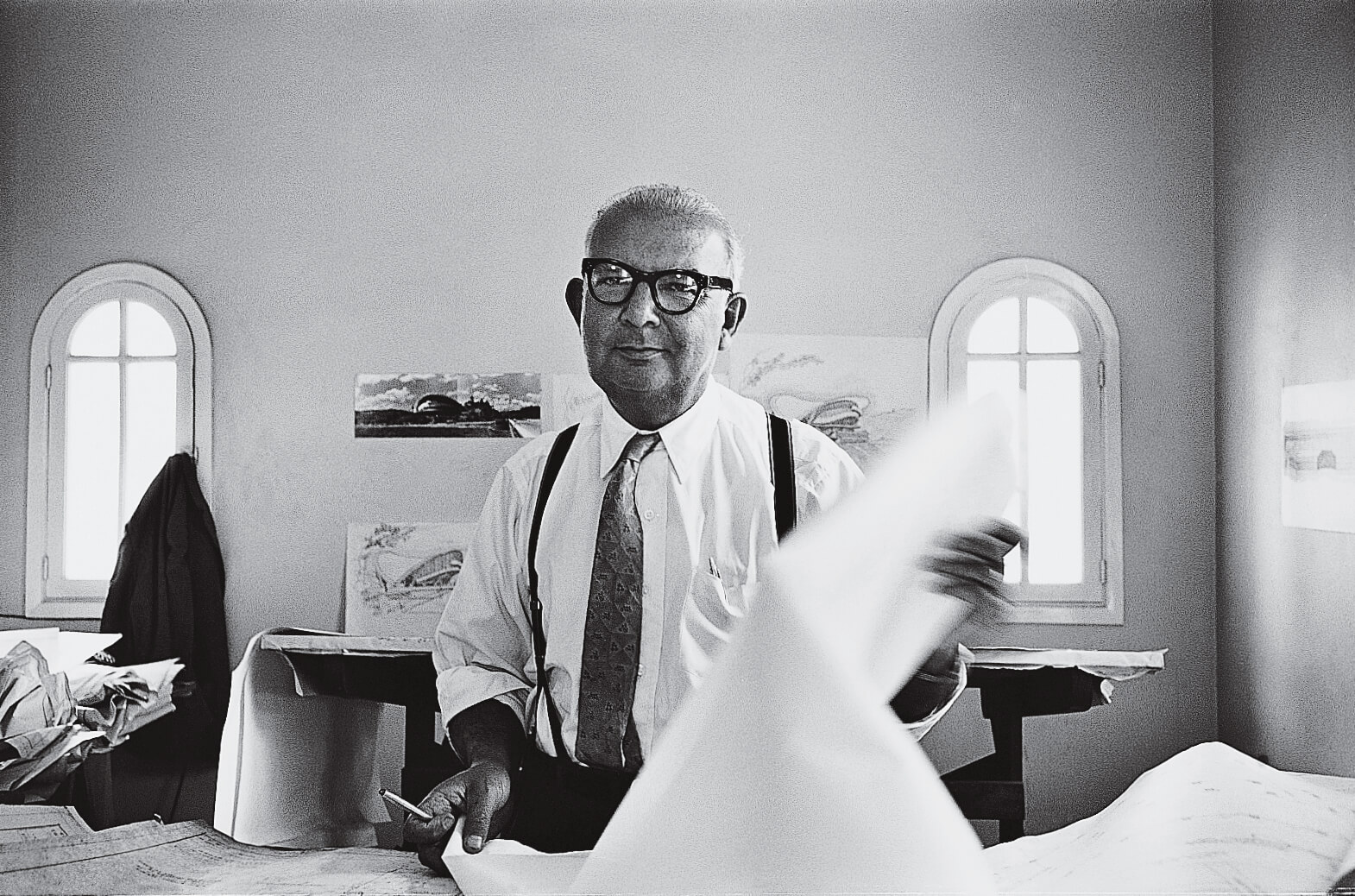

Arquitecto Carlos Raúl Villanueva, creador de la Ciudada Universitaria de Caracas. FV

Los estadios universitarios unidos por la plaza aérea Simón Bolívar, circundados por autopistas. FFU

Vista exterior del Aula Magna desde el jardín de astas de banderas AB

Acceso Facultad de Odontología. GCM

Hall del Aula Magna COPRED.LB

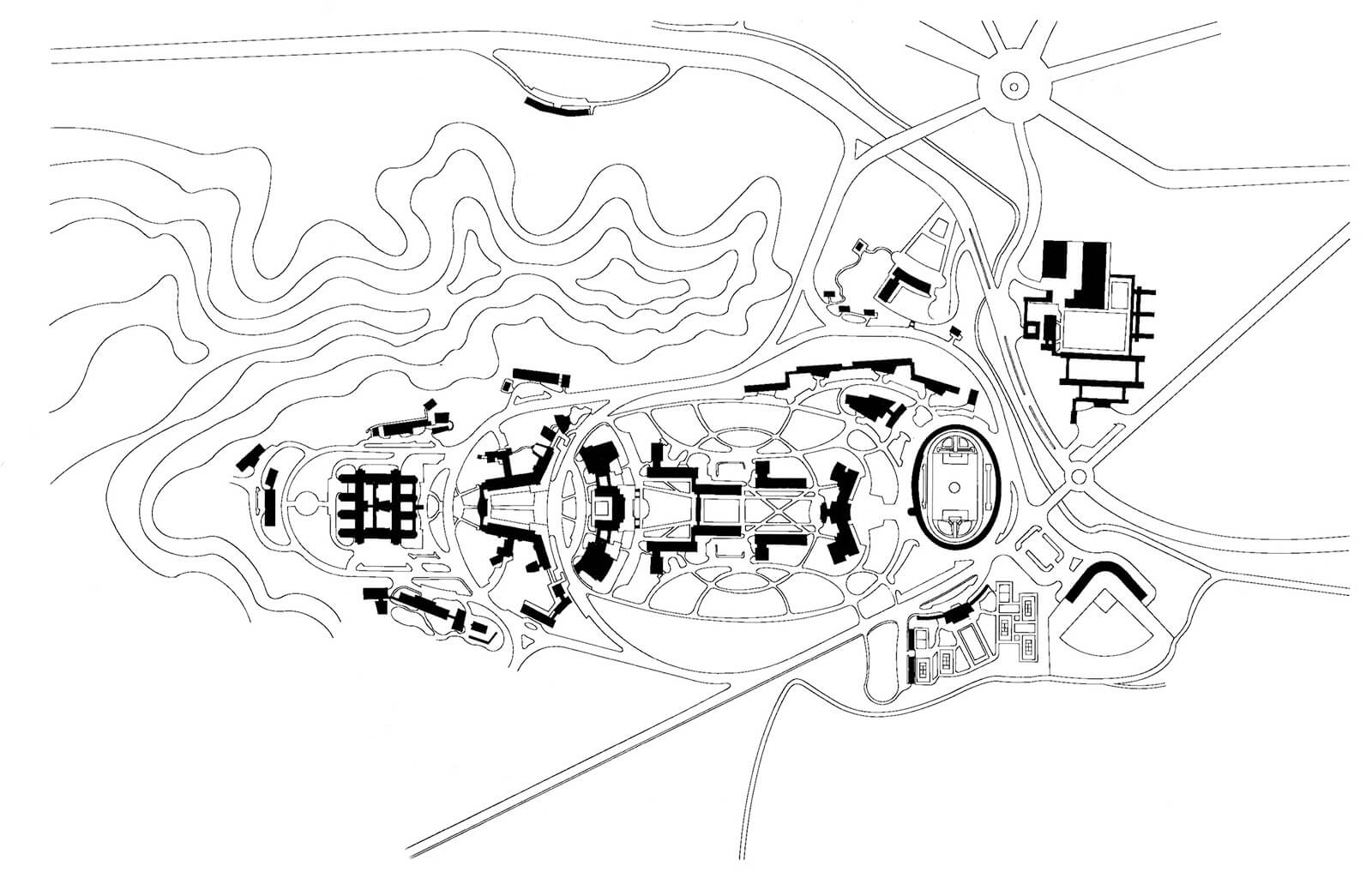

Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas, Plano Conjunto (Beaux Arts), 1944. Dibujo Sandra Fishman. CUC_CU-01

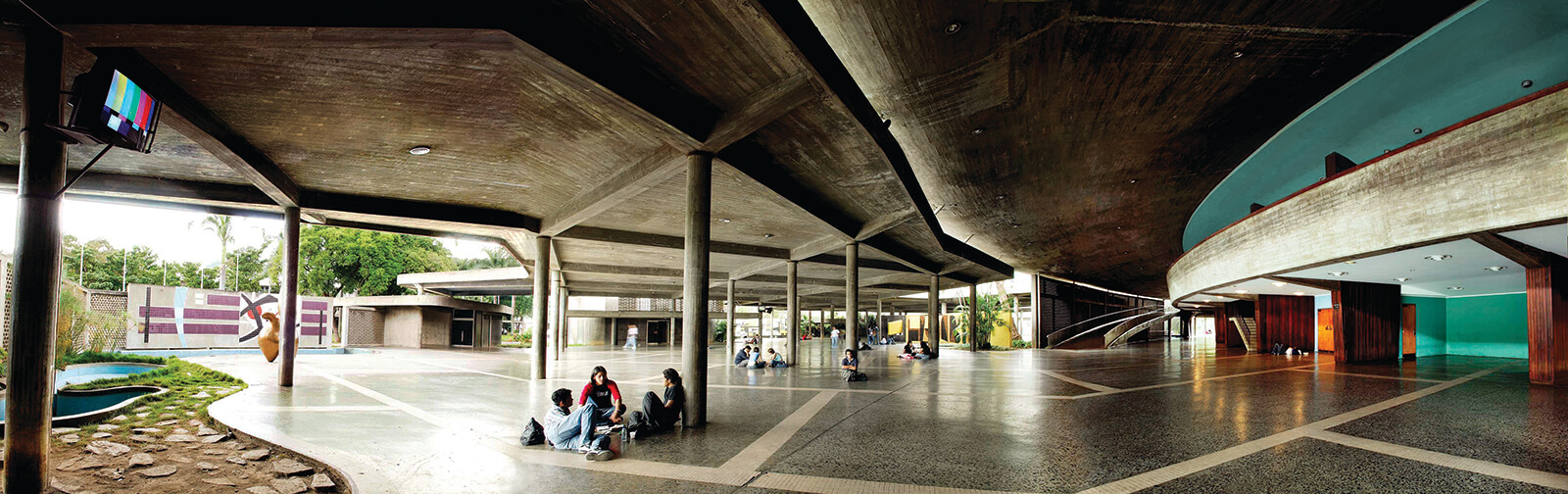

Vista de la plaza cubierta desde el hall del Aula Magna. AB

Rampa de acceso al balcón del Aula Magna. AB

El reloj de la Plaza del Rectorado, símbolo universitario. MEA

Salones de clases abiertos al jardín, Facultad de Humanidades , abiertos al jardín. DDN

Taquilla del Aula Magna y mural de Pascual Navarro, 1954. AB

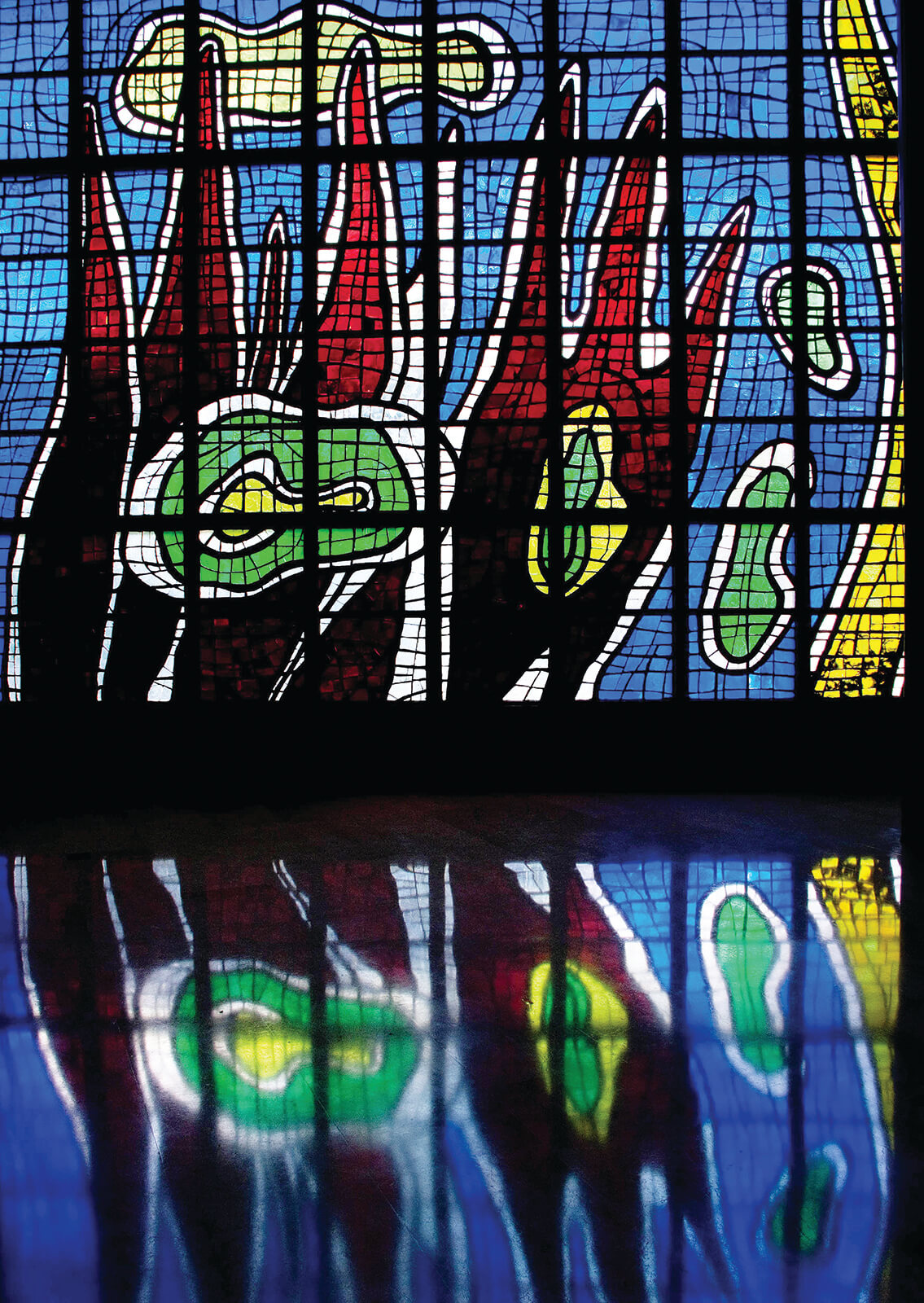

Interacción entre el vitral de Léger y su reflejo en el piso. Biblioteca Central. SUN