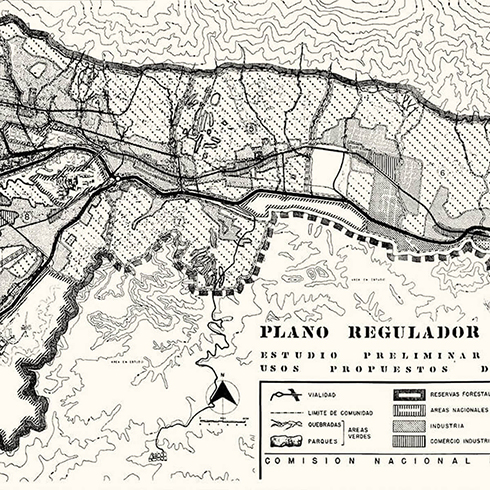

Caracas and its surronds plan, 1941. Librería Caracas, R.N. Ríos y Cía. Edition.HC-49

New urbanisms, new neighborhoods

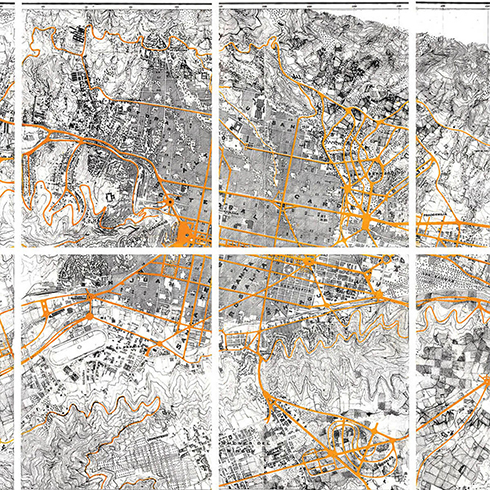

In the 1941 plan, «Caracas y sus alrededores» (Caracas and its surroundings), we observe a collection of new urbanisms exclusively based on roadway systems: Los Chorros, La Castellana, Altamira, Los Palos Grandes, Plaza Morelos, Los Chaguaramos, San Agustín, Ciudad Universitaria, Los Caobos, El Paraíso, Las Mercedes, Nueva Caracas, San Bernardino. This proliferation of shapes has various implications. First of all, a definite celebration of the autonomous urban shape; secondly, the assurance that roadway systems will be determining urban shapes. It is safe to say that the original urban grid has been abandoned and replaced by one more attuned with our geography than with our history.

These proposals for new neighborhoods are traced with a few symmetry axes and some composition principles. In the next few decades, this wish to propose an urbanism with formal values will be lost, and what will remain is the willingness to build with business efficiency.

The isolation, used as a growth strategy by these neighborhoods, produced a peripheral ordering based in segregation, confirming what the 1934 plan augured. To the valley’s east, a new vision of occupation has risen, opposed from the predominant vision of centuries past. Since its beginnings, the Hispanic America subordinated the country to the cities, while the British America conceived its cities as a welcoming and distributing center for the country. In mid XX century, the protestant vision of the noble and healthy countryside, that generated the «little house on the prairie» myth, began to tower over the catholic vision of the holy city surrounded by a profane nature (vision that had generated the checkerboard and the house with a courtyard).

The model of the isolated quinta united with the city by the automobile began to be the aspiration of the whealthy citizens. If formerly the checkerboard house implied a craving for the urban; the detached quinta, carries the seed of our new urbanism, expressing with pride the feeling of rejection towards the city. The grandchildren’s houses begin to be very different form their grandparents’.

El Silencio’s new urbanizing

In parallel to this phenomenon, a new urban reform is goingto take shape with the same strength and political vision that Guzmán Blanco had proposed. Especially in times of Isaías Medina, projects are submitted with a renewal vision, with interventions changing the city’s sense. The most noticeable example is the new urbanizing, concluded in 1945, with a set of multifamily housing units and shops organized in blocks with continuous façade. This development becomes the counterpart of the neighborhoods’ houses known as «quintas» at the city’s east. These buildings at El Silencio adapt to the traditional city’s urban grid, showing big arcades at their perimeter and leaving a big common courtyard at the center. Villanueva is able to adapt the grid’s tissue to the modern city’s proposals. This trend is abandoned just when one of the most notable examples in the history of Caracas’ urbanism is achieved. 3

CAPTION