Zone 10 Facing the sea

Caracas spreads from the valley to the sea…

Caracas is the sum of two scenic geographical components: the mountain and the sea. Crossing from the Caribbean coast to the capital dates back to colonial times and the Way of the Spaniards (1603), the first cobbled road to access the main valley of San Francisco, near Puerta de Caracas and Catia, the closest point to the sea in the middle of the valley. Freebooters were also great researchers of this mountain, with other routes in search of America’s treasures. However, two prosperous sugar and cocoa plantations, Caraballeda and Camurí Grande (1567), were slave population centers and smuggling routes to Petare from the coast. In Venezuela’s central coast, the hacienda was the main form of land tenure up into the nineteenth century, when it became an itinerary for vacationers from the capital.

The day the Caracas-La Guaira freeway (Eugéne Freyssinet, 1953) was inaugurated, the train (built in 1883) and the old road were abandoned. It took about two hours of down hills, from 900 masl to the beach (now it takes 20 minutes). The modernity of the fifties built a new landscape in which mobility had an aesthetic role that traveled the world on postcards. The distances were bridged with two tunnels and three large-span viaducts, with surprisingly light and beautiful designs. Viaduct number 1 was replaced in 2007, after 44 years, with another viaduct of telescopic construction that tripled the distance of the first one (154 m span). Along with the road networks, vacation clubs with outstanding architectural value, and modern elegant installations for public beaches were also built. The city amid parks in the valley was separated from the coastal towns and recreational clubs by an interposed segment of the Coastal mountain range, between the valley and the sea.

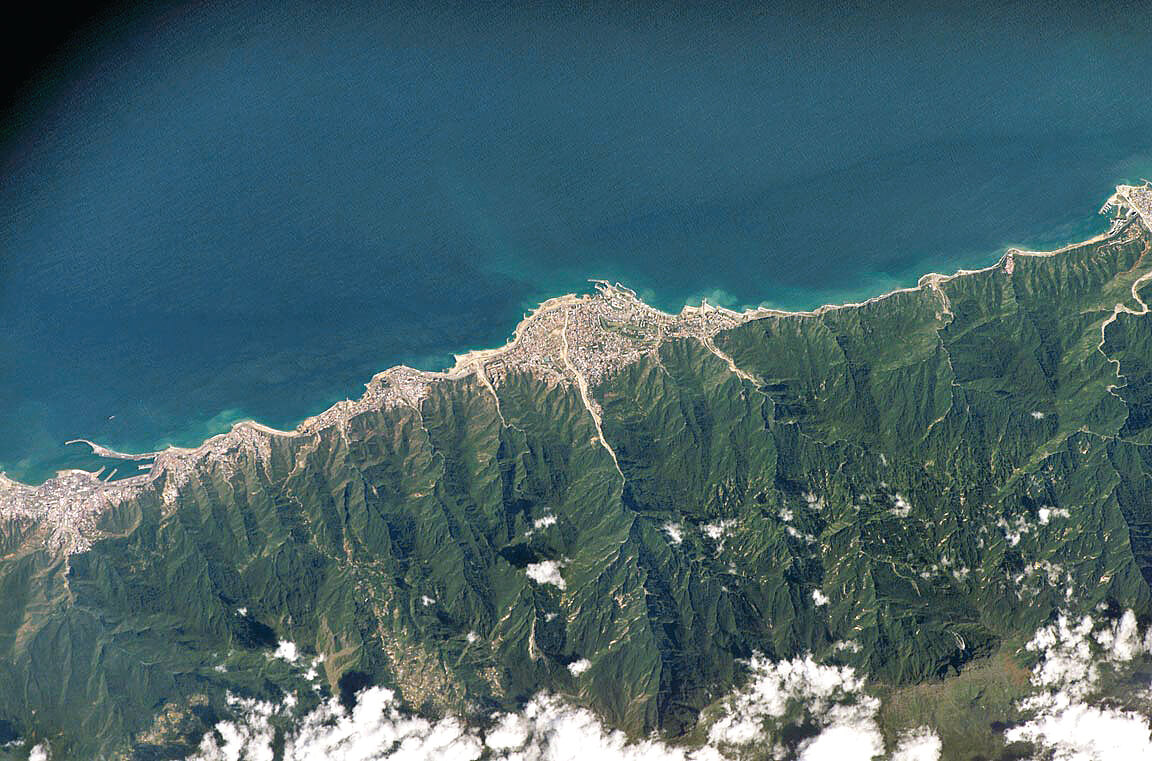

Nowadays, the coast is an extension of the capital, with an 81 km seafront, a distance that triples the extension of the San Francisco valley in Caracas. Various differentiated urban manifestations can be seen in this corridor: Catia La Mar, Maiquetía, La Guaira, Macuto, Caraballeda, Naiguatá and Los Caracas. From this point on, the continuity of the coast and more rural villages continues until Chuspa (47 km), passing through Osma, Todasana, La Sabana and Caruao, where the eastern beltway is completed, to reenter the capital by the Miranda end of Higuerote.

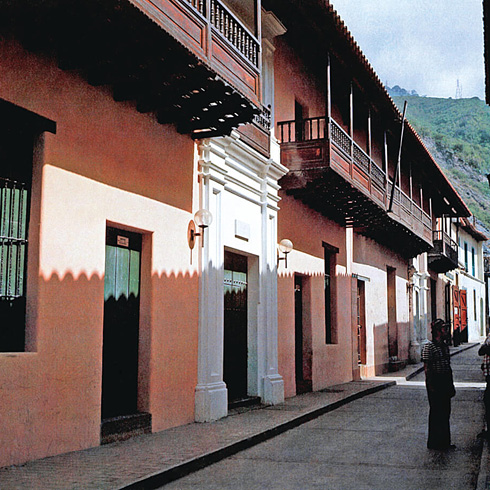

The founding town on the coast (now Vargas State) is La Guaira (1555), a public and cargo entry port, through which the entire country circulated for centuries, with its most important customs house, Casa Guipuzcoana. It was a traditional town with a pattern of irregular blocks, in a fan-shaped layout due to the Osorio creek gully, which divided the town in two, until modernity again imposed a rupture in speed in the east-west direction with the construction of Avenida Soublette (1950), a coastal road that skirted and connected a dozen towns, city-like in some cases and mere informal settlements in others. In colonial

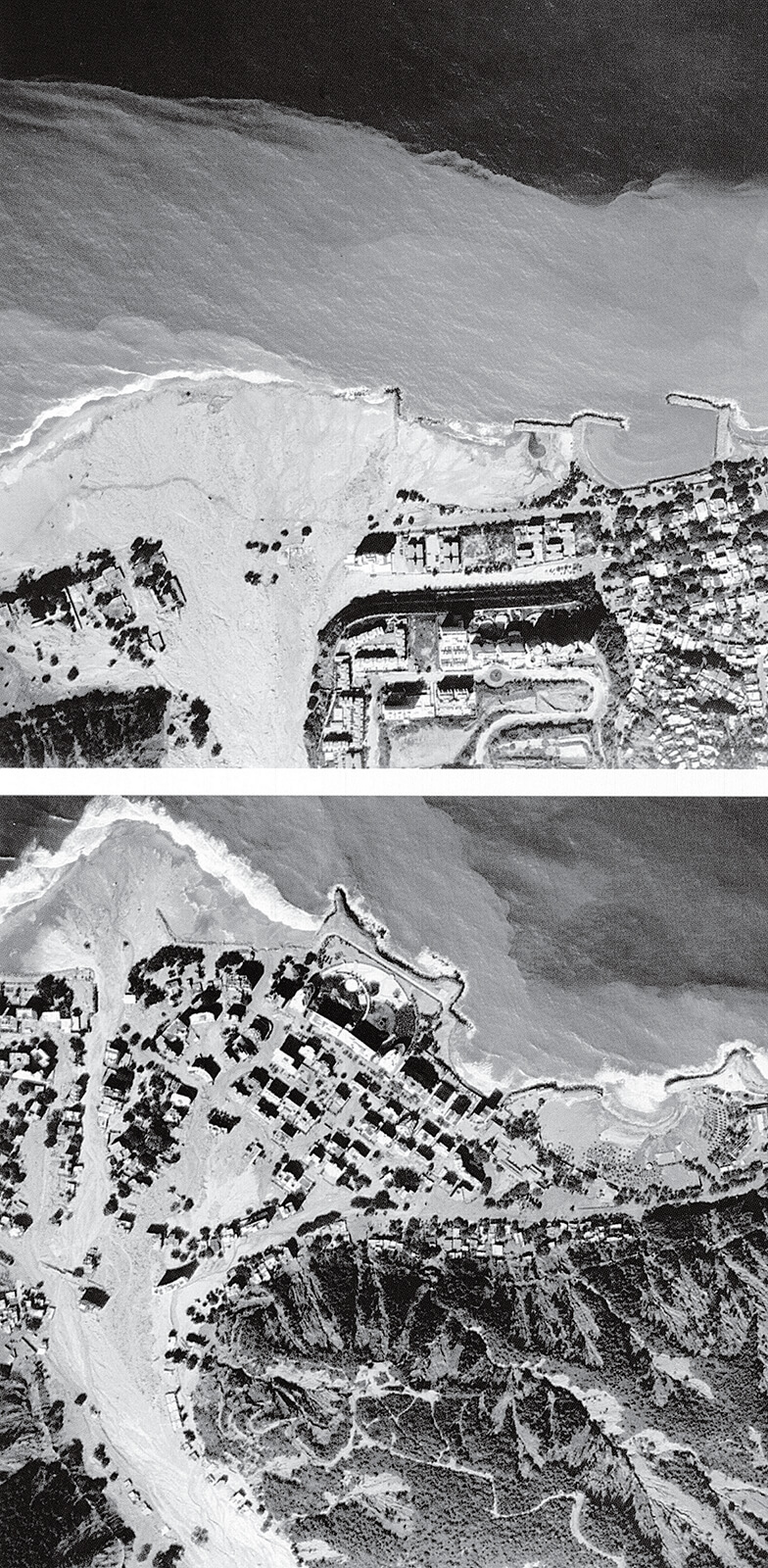

times La Guaira also had a system of fortifications on the road high up on the mountain ridges, which are now immersed in total abandonment, although they are an invaluable heritage. While at one time the Vargas coast was the recreational complement to the capital, it is currently home to a large population that works in the capital and sleeps on the coast. The changes due to the flash floods and mudslides in 1999 (known as the «Vargas tragedy»), which repeated in 2005, left a bad taste towards the forces of nature in its inhabitants, which paralyzed the area’s development for over a decade. Given the general abandonment of vacationers’ properties and the lack of visible reconstruction measures, the coast began fading out for city dwellers, tourists and visitors. Recently, in reaction to the lack of housing in the capital, an aggressive intervention was begun, with the insertion of different format housing of the Great Housing Mission Venezuela (GMVV), especially in Caraballeda with the tallest buildings (twelve stories). The new buildings, still under construction, will bring in a permanent external population -needing shelter as a result of successive natural tragedies- which will leave the people of Vargas out of the game in densifying and occupying their own territory. This will be necessary to complete a new shared urban setting.

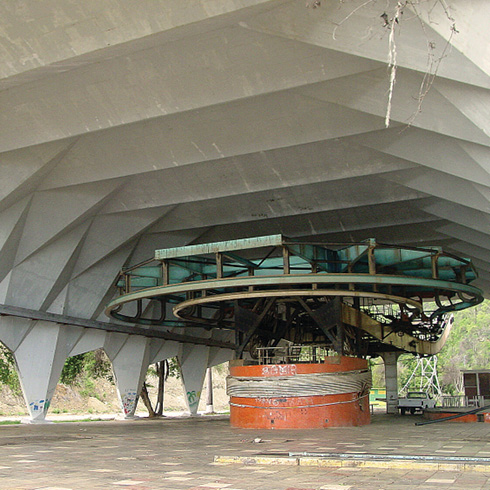

While in Guzmán Blanco’s days Macuto (founded in 1740) was a retreat for elegant tourists from the capital with European-style bungalows (1830-1936) —thanks to the English merchants that came to the capital, repeating the same style in Los Chorros in Caracas—, nowadays the mixture and diversity of urban expressions deserves special attention, to revalue what even today stands out for its architectural or landscape qualities, and make it shine again. Traditionally, Macuto was known for sea and river bathing with a style that remained until the fifties, when two architects, Galia and Alcock, integrated the historic town center to the sea, with the famous promenade of Las Palomas, which was later razed by the mudslides. Although the 1999 tragedy brought a new silhouette to the waterfront, adding coastline naturally —normaly achieved in an artificial and expensive way—, it is also true that nature imposed respect for the riverbeds of some creeks, emptying them of any construction. Meanwhile, the new road system has not yet taken into account the landscaping potential, where the best examples of the valley could be applied on the coast, like Burle Marx’s legacy in Parque del Este, or local examples could be replicated like Las Palomas boulevard in Macuto or the easily restorable Naiguatá and Catia La Mar beach resorts, unlike Puerto Azul and Camurí Grande clubs, and Universidad Simón Bolívar —with its hacienda house—, which have been restored and developed after the changes due to the 1999 event. The beaches have their own dynamics that in many cases has been developing spontaneously, which makes neither their services nor their urban furniture homogenous, nor at a minimum level; however, their natural beauty, including the reefs and small coves with fine sand and native vegetation, contrasting with the Caribbean’s blues, together with the sea breeze, make these beaches a pleasant experience despite the state of the surrounding context, and they are an nearby recreational getaway for the capital dwellers, especially on weekends.

Balneario de Macuto, Siglo XIX. FM-07

Plano del litoral y pueblos costeros. EA-10

Vista aerea sobre la costa (Caraballeda). FM-01

Actual viaducto, Autopista Caracas - La Guaira. FM-03

Vista aérea de efectos de las vaguadas sobre la costa. FFU

Plaza de Las Palomas. FM-08

Playa del litoral central. FM-09

Plano del ferrocarril de La Guaira a Caracas, siglo XIX. FM-06

Viviendas sociales, Gran Misión Vivienda, Macuto. MIP

Vista aérea sobre la costa (Caraballeda). FM-05

Corredor Hacienda Club Caraballeda. DDN

Club Puerto Azul. DDN

Calle del centro colonial, La Guaira. FM-04